Black people are not a monolith, but we are expected to be. When we do not overcome hard times or seek help, the outcome can be detrimental. Drugs and alcohol, while not healthy ways to manage are sometimes the only accessible way to cope resulting in backlash, judgement, exclusion, disappointment, and so forth from the public.

However, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health, African Americans are 10% more likely to report having serious psychological distress than non-Hispanic Whites, yet many do not seek mental health services. For the black community, there is a lot of stigma and shame associated with mental illness (especially for black men).

Growing up in a Black community, black women, in particular, are expected to be caretakers; nurturing, selfless, and supportive—living up to the role of being a “strong black woman”. One would think that as women, often stereotyped as soft and caring, we would be allowed the same vulnerability as white women. However, in my experience, I cannot say that has been the case. How can we be expected to care for others, when we can barely take care of ourselves?

The women I grew up with, the ones who hid in the dark, are suffering now as they try to figure out what went wrong. The men, my dad in particular, is struggling to find peace with himself after so many years of keeping his truth inside.

What about me?

I have many facets to my identity, but it was not until recently that I realized my identity and mental health intersected.

My journey to self-realization as a black woman would never be complete if I did not first recognize and accept the state of my mental health.

Growing up black has its own set of expectations, rules, and pressures to follow. And if it’s unspoken, you will learn soon enough.

For many black people, the aforementioned learned rules are established by the communities we grow up in. In my family, I grew up with women that worked tirelessly and raised children. Who hurt in the dark and let their problems consume them without help. And, I grew up with men that slapped each other the back, and would never be caught with tears in his eyes.

I cannot exclude the role of church and religion in this section. While I did not attend church regularly with my family, prayer and faith was used as refuge for any and all problems. If you just prayed, God had you.

Other than this, the expected language and behavior was never verbalized in my experience but you emulate what you observe.

As a child, I remember my opinions formed quickly. I was vocal, “bossy”, and a little bit of a brat—as hard as that is to admit. To this day, my aunts love to remind me of how I would often roll my eyes and talk expressively hours on end. Besides barking orders or singing Top 40 at the top of my lungs, I was also very emotional. I cried if I couldn’t understand something or complete a task or if I was hurt or not feeling good. Though only a child, I was tapping into emotions that were rightfully mine.

My teenage years brought a whirlwind of doubt and self-consciousness. At school, I was teased about my appearance and the way I talked. This time period is as early as I can remember dealing with anxious thoughts and shying away from what I used to be—that loud and cocky 5th grader.

When we think about anxiety, we mainly think nerves that pass. It is not often taken seriously, mainly because it’s difficult to describe. From my experience, however, it is all encompassing and debilitating. It challenges you and mocks you. Berates you and makes you feel crazy. And I definitely felt crazy. Yet, I ignored it until I could. I was ashamed to feel what I felt. “I should be stronger than this”, I would think. Being strong is all I knew, but I was breaking. “I can’t do this,” is what I eventually declared.

What felt like giving up was only the beginning of what I needed.

My story is still unfolding and adding its own layers. After my revelation that I was not “okay” I sought help where I could. I wrote journals and cried to my parents, who helped me as much as they could. I am a product of the environment in which I grew. I will still make mistakes. I will still take medicine to find balance. I will still stumble and I am allowed to. And so are you.

There is so much to unpack with this subject and I know I have failed to cover it all, but that just means the work is far from over. I am fortunate to have the resources to help myself, but I am one of few. How can start listening to one another? How can we make resources more accessible for those who need them? It will take time and work to dismantle the problems in our community.

Until then, the first step is accepting you deserve help.

The second step is starting the process of taking care of you.

Mental health is not one-size-fits-all. One’s ethnicity, sex, race, values, religion, community all play a major role in determining how an individual responds to the challenges of mental health. As you can imagine, these differences can make mental health treatment much more challenging. To recognize these challenges and promote public awareness of mental illness in minority communities, National Minority Mental Health Awareness Month was established in 2008.

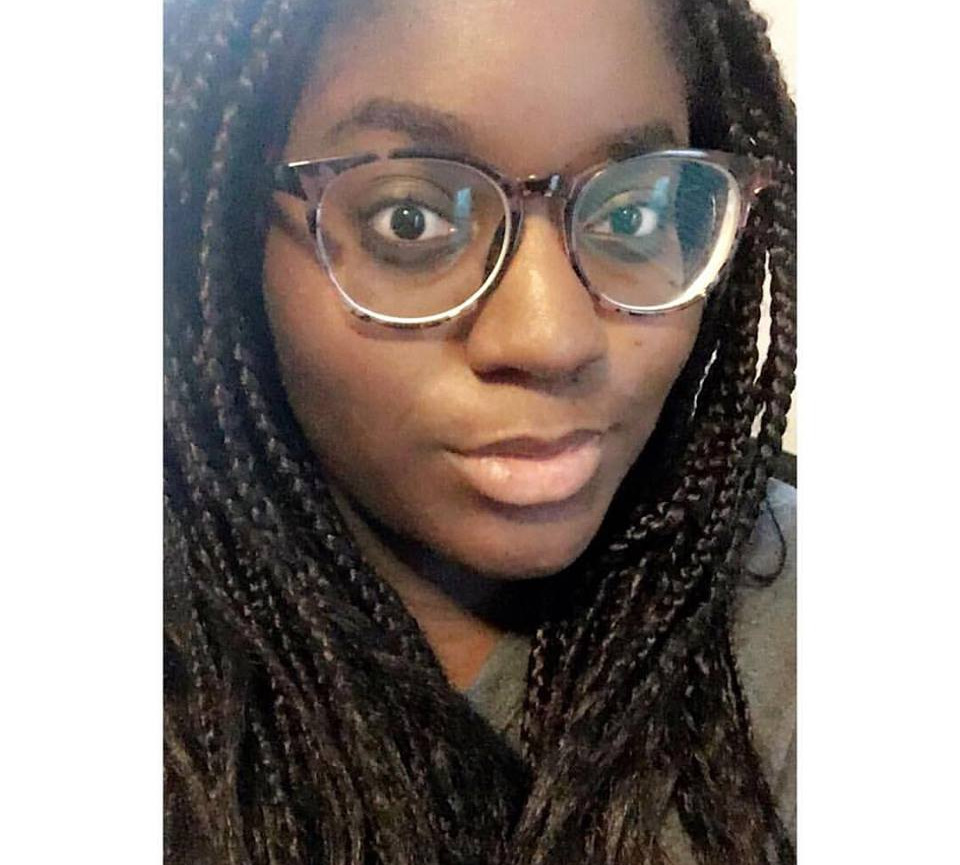

Special thanks to community member Chantal Johnson for sharing her experiences recognizing and managing her mental health while being black. Check her out @chantalks and on YouTube.

Chantal Johnson is a young writer and aspiring author hailing from Roanoke. When not watching a ridiculous amount of British reality television or thinking about Beyoncé, she writes about pop culture and its influence on society and mental health.